- Published on

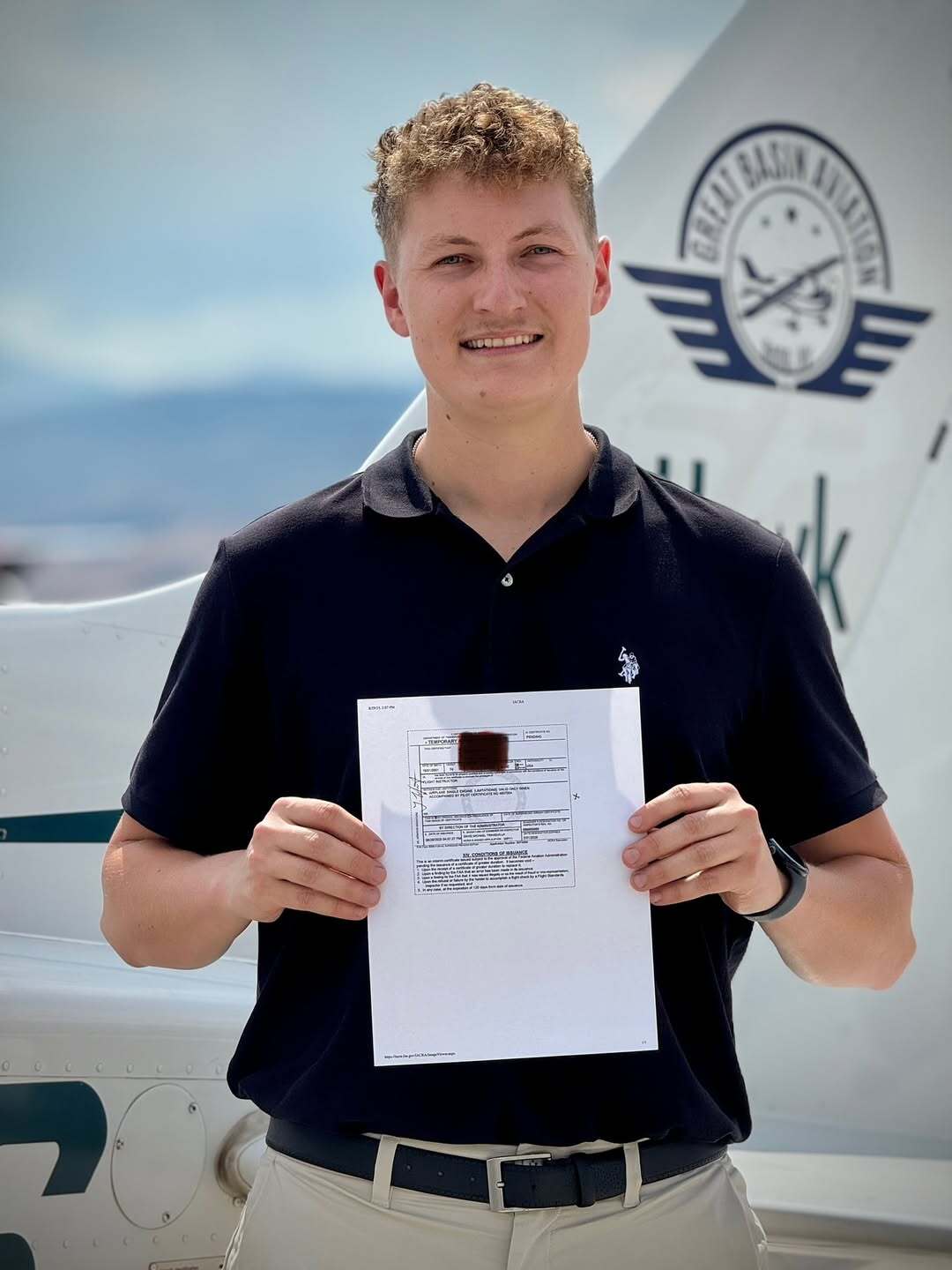

Huge congratulations to Troy Cook on earning his Private Pilot License today! This is a huge milestone and a true testament to Troy’s dedication, persistence, and willingness to put in the hard work to achieve his goals. This accomplishment reflects months of discipline and determination, a challenge Troy is used to as a business owner himself.

Outside the cockpit, Troy is a man of many skills, from blacksmithing, carpentry, welding, and commercial fishing to truck driving and ski coaching. He’s not afraid to get his hands dirty, and he brings that same grit and determination to everything he does. He’s also an explorer at heart, always chasing the thrill of seeing new sights. Whether it’s from the cockpit, on skis, a snowmobile, or out on a hiking trail, Troy lives for the adventure. As a business owner and now a licensed pilot, Troy continues to prove that hard work and adventure go hand in hand, and that the sky is only the beginning.

Troy’s journey proves that with hard work, a love for adventure, and the courage to take on new challenges, the sky truly has no limits. A special shoutout as well to his CFI, Lucas Murphy, for guiding him on this journey and helping him reach this achievement! Every great pilot has a great teacher behind them, and today they both share in this achievement. Congratulations again, Troy, the sky is yours!!

Outside the cockpit, Troy is a man of many skills, from blacksmithing, carpentry, welding, and commercial fishing to truck driving and ski coaching. He’s not afraid to get his hands dirty, and he brings that same grit and determination to everything he does. He’s also an explorer at heart, always chasing the thrill of seeing new sights. Whether it’s from the cockpit, on skis, a snowmobile, or out on a hiking trail, Troy lives for the adventure. As a business owner and now a licensed pilot, Troy continues to prove that hard work and adventure go hand in hand, and that the sky is only the beginning.

Troy’s journey proves that with hard work, a love for adventure, and the courage to take on new challenges, the sky truly has no limits. A special shoutout as well to his CFI, Lucas Murphy, for guiding him on this journey and helping him reach this achievement! Every great pilot has a great teacher behind them, and today they both share in this achievement. Congratulations again, Troy, the sky is yours!!